[I own DoorDash stocks. This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence.]

The Deal

Mainstreet news media report the deal as such: “Amazon Bringing Grubhub To Prime Users After Buying 2% Stake”, “Amazon buys 2% stake in Grubhub, offering new perk for Prime members.”

Astute investors study source materials. According to Grubhub’s official newsroom release:

- Amazon Prime members in the U.S. can sign up for a free, one-year Grubhub+ membership — i.e., $0 delivery fees on orders of $12+;

- Amazon receives warrants (exercisable at a de minimis price) over 2% of Grubhub;

- Amazon also receives warrants (exercisable at a formula-based price) over up to an additional 13% of Grubhub.

Let me rephrase these details: Amazon receives an option for free, which lets Amazon get 2% of Grubhub’s equity for free. And if Amazon wants more, Amazon can purchase another 13% of Grubhub’s equity for an undisclosed price. Amazon can choose to move forward or back out. There is no commitment.

Another way to view this deal: Grubhub launched a marketing campaign to acquire users, by giving away its Grubhub+ membership for free on Amazon’s Prime website. For Grubhub, the cost of this marketing campaign is to give away 2% of its equity for free to Amazon, without receiving any firm commitment from Amazon at all.

Why Did This Deal Happen?

For Grubhub, Grubhub is desperate to find growth: From 2019 to today, Grubhub’s market share has been in a non-stop decline, shrinking from ~25% to now under 15%. This all took place despite Grubhub’s active efforts to arrest this negative trend:

- Oct 2020: Grubhub started offering Grubhub+ membership for free to Lyft Pink members.

- Aug 2021: Grubhub started giving Grubhub+ Student membership for free to Amazon Prime Student members.

- Nov 2021: Grubhub started offering one year of free Grubhub+ membership to Instacart+ members.

In 2022, things turned a bit dramatic. On Feb 23, 2022, Grubhub put out a press release titled “Grubhub Launches Ultrafast Delivery in Partnership With Buyk” (source link). The following week, Buyk furloughed almost all its employees! In another two weeks, Buyk filed for bankruptcy!! Not a good sign for Grubhub.

Coming into Jun 2022, Grubhub CEO Adam DeWitt said in a conference: “[For Grubhub,] It is finding a strategic partner. Finding channel partners. It is about finding a way to help Grubhub grow…” (source link).

For Amazon, Amazon is accustomed to doing deals with “warrant” elements: In its history, Amazon has done “at least a dozen deals with public traded companies” in which Amazon gets warrants; moreover, Amazon has done more than 75 similar deals with private companies (source link). So, it is fair to argue that this Grubhub/Amazon deal might not contain much “signaling value.”

For Amazon, Amazon wants more perks for its Prime members: Amazon’s number of Prime members has stopped growing in the first half of 2022 (source link). Making it worse, the 30-day renewal rate for Amazon Prime membership has been falling in recent years (source link). It is sensible to argue that Amazon is facing pressure to convince its Prime members to stay, especially after the fact that Amazon just raised U.S. Prime membership price in early 2022.

This year marks the 3rd time Amazon raised Prime membership prices — $79 a year in 2005, $99 in 2014, $119 in 2018, and $139 now. But this time, the environment Amazon finds itself in is a bit different. The U.S. market is much more saturated for Amazon than ever before. Amazon now has 150M to 200M Prime members in the U.S. while the total U.S. population (including infants and elderly) stands at ~320M. The U.S. is also experiencing the worst inflation in decades and Amazon consumers feel the need to cut back on spending. So, it is reasonable to argue that Amazon is also pressed to find ways to add more benefits into its Prime program so as to retain Prime members. Therefore, Amazon is motivated to have this agreement with Grubhub now.

Why May This Deal Not Matter Much?

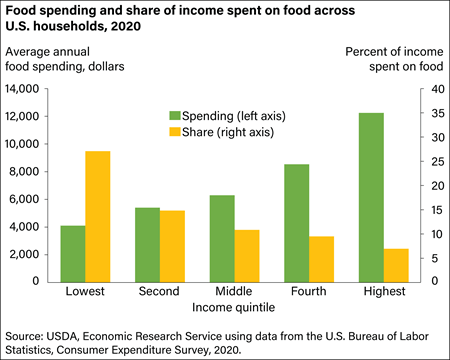

For Grubhub, it is too late: By income level, the top 20% of U.S. households spend ~7% of household income on food, annualized at ~$12K per household per year; the bottom 20% of households spend ~27% of household income on food, annualized at ~$4K per household per year (source: USDA; see chart below). The rich spend 3x more money on food, in terms of dollar spend. Yet, as a percentage of their income, the rich spend ¼ the size of spend that the poor put on food. Pay attention to the disparity between the $ and the %.

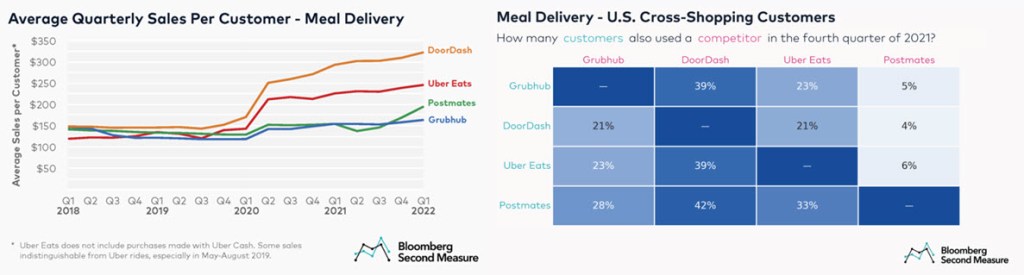

Making it more interesting are two particular user behavior patterns. DoorDash users on average spend ~2x as much dollar ordering food delivery on the DoorDash app than Grubhub’s users do on the Grubhub app; and, among major food delivery apps, DoorDash has the most loyal users who use other food delivery app the least (source: Bloomberg Second Measure).

So, combining these observations with what I have learned in other non-food-delivery ecommerce verticals, if I am allowed to “conveniently” categorize consumers, I will propose that there are two types of consumers:

- Type A: People with a lot of money but very little time.

- Type B: People with not that much money but a lot of time.

Type A consumers are the top 20% most wealthy households. Those are the consumers that possess the highest purchasing power, and usually, have busy lifestyles — which means they treasure the convenience of food delivery, and they have little time or motivation to compare prices across various food delivery apps.

The U.S. has ~120M households. So, 20% of that is ~24M households. DoorDash official number is that DoorDash has over 25M monthly active users (MAU). Think about it. Connect it with the fact that DoorDash users are spending more on the DoorDash app and looking at other food delivery apps less. It is sensible to say that most DoorDash users are Type A.

The other side of the coin is Type B consumers. They would tend to perceive food delivery as a luxury service and they would have both the economic incentive, and possibly, the time, to cook for themselves at home. Having less money but more time also means if they want to order food delivery, they will compare prices across food delivery apps. Therefore, we observed that Grubhub and Uber Eats users are not loyal to these two apps. And because DoorDash is generally cheaper to use than Grubhub and Uber Eats, DoorDash actually has a powerful appeal for less affluent consumers too! (More on DoorDash’s cost advantage later.)

Is DoorDash unaware of this differentiation of consumer wealth? I think not. The answer is probably the opposite — I argue, DoorDash has been pursuing an explicit strategy to go after the wealthiest consumers first. In 2019, DoorDash acquired Caviar, a premium food delivery platform that connects high-value diners with upscale restaurant brands. Until 2022, the acquisition of Caviar was the single biggest acquisition in DoorDash’s history.

DoorDash knows what it is doing. For Grubhub, it is too late.

For Amazon, it has never achieved meaningful success in food delivery: There are two major episodes in Amazon’s history that shows Amazon’s intention to enter the food delivery space. Neither has had meaningful success.

In 2015, Amazon launched its own food delivery service in Seattle, called “Amazon Restaurants.” After expanding to 20 American cities and London, Amazon shut down its food delivery program in 2019. On paper, Amazon’s strategic position looked great:

- Existing “Amazon Flex” delivery drivers.

- Existing Amazon users.

- Like other food delivery platforms at that time, Amazon charged restaurants commissions (~27.5%) and charged consumers fees ($2.99 and $4.99 per order).

- In Apr 2016, Amazon Restaurants launched in San Francisco. At that time, DoorDash was only three years old and had raised in aggregate ~$200M. Amazon’s market cap was then $300B.

Despite all these apparent advantages, Amazon Restaurants never took off. For most cities, Amazon Restaurants’ market share was so small that it was not visible on charts.

Amazon’s second episode with food delivery is its involvement in UK food delivery. In May 2019, Amazon led a $575M funding round for UK food delivery platform Deliveroo, taking a 16% equity stake in the UK company. In Sep 2021, Amazon announced that it would start offering Prime customers in the UK free Deliveroo Plus membership — i.e., free delivery on orders over £25. Guess what happened? Deliveroo’s market share and user retention, neither has seen material improvement.

Why has it been so hard for Amazon to succeed in food delivery? I think there are three reasons.

One, Amazon is built to deliver goods, using a hub-and-spoke model, on a daily schedule. Amazon is not built to deliver services, from anywhere to anywhere, on an anytime schedule. It is really hard to ask Amazon drivers, who are accustomed to moving packages between a central warehouse location and a defined delivery route, to do what food delivery drivers do: to pick up food from restaurants that can be located anywhere, and then to deliver this pack of food to customers that can be located anywhere; all this must be done within ~35 minutes and handled with great care, so the food does not spill or turn over, and still tastes good. To repetitively do this at a scale, that is not what Amazon is built for.

Two, Amazon does not have the consumer mindshare. When people feel hungry, they do not think of Amazon first. People do not associate Amazon with restaurant meals. Let’s take Google as an example. Do you know you can order food delivery on Google Maps? Not a joke. Since 2019, Google Maps has had a food delivery function. But have you used Google Maps to order food? It is a mindshare problem.

Three, Amazon has its fingers in too many jars. As a behemoth, Amazon is fighting too many wars at the same time, ranging from movie production to cloud computing. This complexity means prioritization is a challenge. It is hard for a large organization like Amazon to dedicate enough attention and resources to one single front. Amazon is fighting wars on too many fronts.

Time Is DoorDash’s Friend

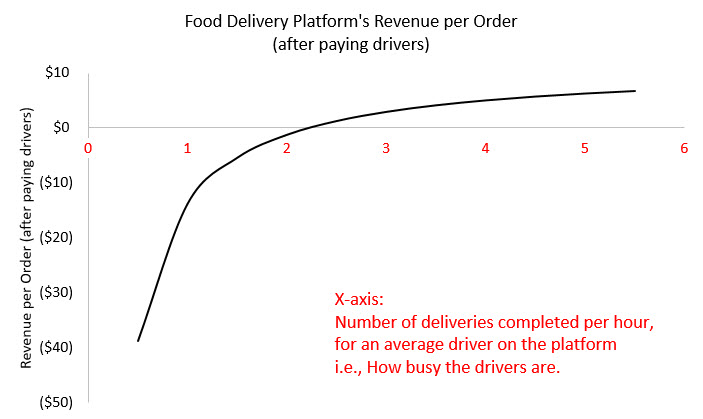

I made the above chart to illustrate a fundamental aspect of the food delivery business:

- If a platform has no scale, it bleeds cash: On the left hand side of the chart, a platform can lose $10 to $20 per order easily. Note, I am talking about revenue, not profit.

- If a platform has scale, it prints cash: On the right hand side of the chart, a platform can make $1, $2, or even more revenue per order. And because drivers are already paid, a large portion of the revenue dollars drop directly to the bottom line, resembling a software business.

I built this chart using my modeling data, which is grounded in DoorDash’s public data in its public filings. For most food delivery platforms, due to inefficiencies (such as a higher level of order refunds), their “curves” look much worse than this one.

Imagine a no-scale food delivery network, say, it handles 100M delivery orders a year (as a reference, DoorDash completed ~1.4B orders in 2021, the vast majority of which were delivery orders). Without scale, such a platform probably registers -$5 to -$10 revenue per order, thus a negative revenue of -$500M to -$1B per year. That is the topline, before any corporate expenses. That’s billions of dollars of losses per year. That is why DoorDash has a moat, a deep moat.

As DoorDash accumulates more users and more transactions, food will be delivered faster and cost will come down as well (due to efficiency gains, such as eliminating order failures). Therefore, as time goes by, consumers will experience faster and faster delivery speed, lower and lower delivery cost. DoorDash becomes a service-quality leader, while also becoming a cost leader and a price leader. And, at the same time, DoorDash will make more and more money. That is why I say, time is DoorDash’s friend.

Try ordering food now on the DoorDash app, and placing a similar order on the Grubhub app. Count the time you spend waiting for the food. Count the dollars you spend. Compare the two platforms. You will see what I mean. DoorDash is both cheaper and faster.

Lastly, let me make a bold prediction. Given DoorDash’s market cap of ~$30B today, within the next ten years, on a nominal/undiscounted basis, DoorDash’s GAAP profits from its core U.S. food delivery business, cumulatively over the ten years, will be bigger than its market cap today.

For DoorDash, whether to show a GAAP profit or not is a choice. It is DoorDash’s own choice to reinvest GAAP earnings back into its business, so DoorDash currently shows a GAAP loss. For its core food delivery business, DoorDash is already highly profitable on a GAAP basis. If it wants, DoorDash can show a GAAP profit in FY2022. Beyond FY2022, it can show GAAP profits in the scale of billion of dollars.

That is why the Grubhub/Amazon deal is not a big deal. That is why I am bullish on DoorDash.

(END)

[…] Update on Grubhub/Amazon Deal: Starting Jul 6, 2022, Amazon Prime members in the U.S. are given a free, one-year Grubhub+ membership with unlimited free food deliveries. This arrangement effectively brought the e-commerce behemoth back into the U.S. food delivery arena. To me, it served as a “stress test” on incumbent players such as DoorDash and Uber Eats. And three days later, on Jul 9, 2022, I made the public prediction that the Grubhub/Amazon deal would NOT matter (see my blog here). […]

LikeLike

[…] basis) since 2020. Whether to show GAAP profitability or not, as I wrote in another piece in 2022 (link), is a “choice.” Take this past quarter of 2024 Q2 as an example. On the one hand, DoorDash […]

LikeLike