On April 19, 2020, I became convinced that over the next two days, prices of crude oil would drop below $0. The next day, April 20, oil opened at $17.73 a barrel and closed the day at negative -$37.63 a barrel.

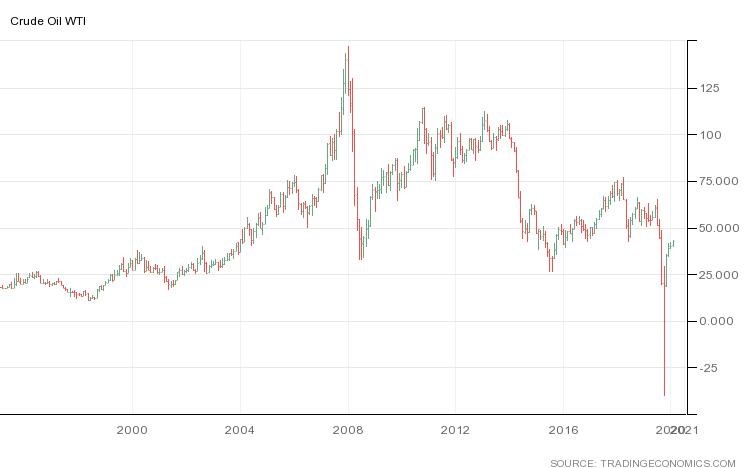

To help us appreciate the magnitude of that epic collapse, the oil price chart below showing the past 25 years would be helpful. See that big plunge?

To be clear, I am not an oil expert. I never worked in the oil industry. For the past many years, I have never visited any oil field nor spoken with any person who work in the oil industry. Even until today, I have never seen a barrel of crude oil with my own eyes.

So, how did I successfully predict negative oil prices? It’s a bit of story.

“Go Buy Oil! I’m ALL IN!”

In early March this year, Russia and Saudi Arabia got into an oil price war, sending the price of oil under $30 a barrel. A friend of mine poked me and suggested that oil is a good investment — it was a simple and convincing idea: oil had become too cheap, too attractive.

Within the next few days, oil further weakened to around $19 a barrel. What does $19 a barrel mean? No time in the past 10 years oil traded below $20 a barrel. No time in the past 20 years either! That piqued my curiosity in oil — specifically, in buying oil.

Why buying oil? I believe oil was unusually cheap and oil could not stay at the present level for too long. The U.S., Russia and Saudi Arabia, these three countries dominate the world’s oil production with a total market share of about 40%. All three countries have strategic relations with oil. In the U.S., the shale oil industry bears strategic importance for the nation’s energy independence and is also a key economic driver for a few large states. However, shale oil is known for its notoriously high production cost; shale oil producers are known for their highly leveraged balance sheets. A sub-$20 oil price could bankrupt the shale oil industry and cause large-scale unemployment. So, oil prices could not stay that low for too long, I reasoned.

For Saudi Arabia and Russia, what really matters is their “fiscal break-even oil price” as both countries are highly reliant on oil incomes. There are various views on this, but almost all sources agree that the two countries’ break-even oil prices are way above $20 a barrel, if not a few times over. A sub-$20 oil price, if it lasts an extended period, could potentially bankrupt these countries. So, oil price could not stay that low for too long.

These high-level analyses led me to conclude that, as long as 2020 is not the end of mankind, the price of oil will and must recover relatively quickly to its “normal levels,” like $40 a barrel or above. That implies a quick return of over 100% if I buy oil now. What a great idea!

That was the weekend of April 18, 2020. I decided that I was going to go all-in with oil.

Wait a Night

For big ideas, I tend to sleep on them before making a final move. I benefited from this behavioral pattern many times in the past and this time was no exception.

Lying on the bed and waiting to get into sleep, I kept mulling over this “buy oil” idea and asking myself on what basis I could end up losing money. I knew price will be volatile in the near term. I knew price will eventually recover in the long term. I had no problems with these two. But was there a third scenario out there that I didn’t see?

And I kept asking myself: how can I get seriously harmed if I buy oil now? My account goes to zero… that would be bad. Can it get worse? Can I owe someone money if things go terribly wrong? Hmmm…

That thought sent a chill down my spine. I jumped out the bed, ran to my computer and Googled “negative oil price.” Guess what I saw?

CME Group (April 15, 2020): Testing Opportunities in CME’s “New Release” Environment for Negative Prices and Strikes for Certain NYMEX Energy Contracts

https://www.cmegroup.com/notices/clearing/2020/04/Chadv20-160.html#pageNumber=1

Hmmm… interesting… The exchange on which oil trades tested their system for “negative price.” These people might know something I do not know. I kept reading on CME’s website until I arrived at the “contract specs” page. And I saw something that I knew long ago, but I didn’t really think about it until then — crude oil futures contracts are “physical” contracts. It means if you are long crude oil futures contracts on the expiration date, you are obligated to physically accept barrels of crude oil. Yes, physically, in the most literal sense, at a place called Cushing, Oklahoma. And to accept delivery, you need to have storage space ready. Oil needs storage space.

This “oil needs storage space” train of thoughts led me to another round of Googling that night, searching keywords like “oil storage cost,” “oil storage space availability.” All search results pointed me to one direction: the world was running out of storage space.

How could I be sure I was getting the right information from the Internet?

I am always skeptical on opinion pieces that I read on Internet. There are too many opinions flying around these days on Internet. I am not an oil expert. I do not know any person working in the oil industry who I can call and ask for help. It was late into the night and it was a weekend — how could I independently and immediately verify that the world was about to run out of storage space?

Price… price… what’s the current price of oil… I mean what’s the spot price of oil now in the U.S… not the price at nearby gas stations but the price people working in the oil industry pay… the spot price…

I typed “oil spot price” in Google. And within a second, I saw multiple news articles reporting that prices of spot oil had lowered into low single digits, like $2 a barrel, in multiple locations across the U.S.

That “$2 a barrel spot price” convinced me that there was a real shortage of oil storage space.

I suddenly realized that for most people who were still long crude oil futures, they would likely run into troubles because there would be no storage space left for them to take crude oil deliveries.

When would the forced selling happen? How to time it? I went to CME’s website again and looked at the soon-to-expire oil contract. Its expiry date was April 21, 2020 (Tuesday).

If I was right, on or before April 21, 2020, the people who were long the near-term crude oil futures would “wake up” and realize that there would be no oil storage space for them in Oklahoma. And if they could not fulfill their “obligations,” they must get rid of these “obligations” — they would become the forced sellers of the near-term futures contracts…

I saw it! I saw it!

I saw an epic wave of sellers that the world had never seen before… arriving… on either April 20 or April 21…

There would be few buyers on these two days… People were running out of storage space…

Oil would collapse… into the negatives… It would be epic!

Aha! That was why CME tested their systems for negative prices…

I saw the vision. I saw it.

I told a few friends my ideas. They told me I was crazy, and I should go to sleep.

The rest is all history.

Reflection

I saved myself from a huge financial disaster and instead turned it into probably one of the best ideas that I ever had. (The other contender is my prediction of Uber’s failure in China, see here.)

What did I learn from this experience?

1. Price is ultimately determined by supply and demand, not by people’s opinions. The price of oil collapsed into the negatives despite the overwhelmingly one-sided opinions held by almost all people that “oil was too cheap.” If a market has no buyers but only sellers, price collapses. Economy 101.

2. Asset can become liability in a snap. We must know what we own. Some securities have a bipolar nature and you need to know it before it is too late.

3. Be very flexible and be open-minded. Challenge your own thoughts. If it is a big and important decision, please mull it over again and again. Also, be ready to act very quickly.

A secondary question is: why did most people not see the negative oil price coming? The brokers, traders, asset managers, oil experts…

Here are my answers:

1. Separate opinions from facts. When we think, think in facts. Do not think in opinions. Opinions are usually products of “first order thinking,” especially opinions that have not been updated for years. They are usually littered with obsolete knowledge and they are often biased because of the owners’ preconceived notions of “how things should always be.”

2. Be very open-minded. Something that has never happened before does not mean it cannot happen in the future. Just because you don’t believe it does not mean it will not happen.

3. Apply a lot of common sense. Think independently on your own shoulder.

(End)

[…] that I successfully predicted negative oil price in April 2020. See my previous blog piece here (link). Following that event, a friend of mine said this to me, “Jackson, had you consulted industry […]

LikeLike

Excellent post. Very valuable reflections.

LikeLike