I observe myself and my investment activities and outcomes. I also observe other active investors and their investment activities and outcomes (this was actually my full-time job before). Something I noticed perplexes me: Despite almost all active investment managers being highly educated, well trained, and extraordinarily hardworking, almost all of them (at least in the U.S.) end up underperforming stock indexes.

For example, for the past 20 years, over 97% of “Large-Cap Growth Funds” in the U.S. underperformed the S&P 500 Growth Index; and the longer the measurement time window, the higher the percentage of underperformance (source: link). According to another source, losing funds’ underperformance is about 2x the size of winning funds’ outperformance (source: Figuring It Out, Ellis). To put it differently: Most investors end up underperforming, and when they underperform, they underperform by a wide margin. Clearly, investors’ hard work has largely failed to translate into good results. Why?

Serious studies have been made to identify the exact reasons. Answers range from Regulation FD, market efficiency, stock concentration to the top, etc. The list goes on and on. I do not disagree with any of these. However, let me offer some additional perspectives. They are my personal views. They appeal to common sense yet they are somewhat counterintuitive. They are abstract and they lack exactness. Collectively, I call these ideas of mine the “invisible path.”

The Relationship Between “Effort” and “Results”

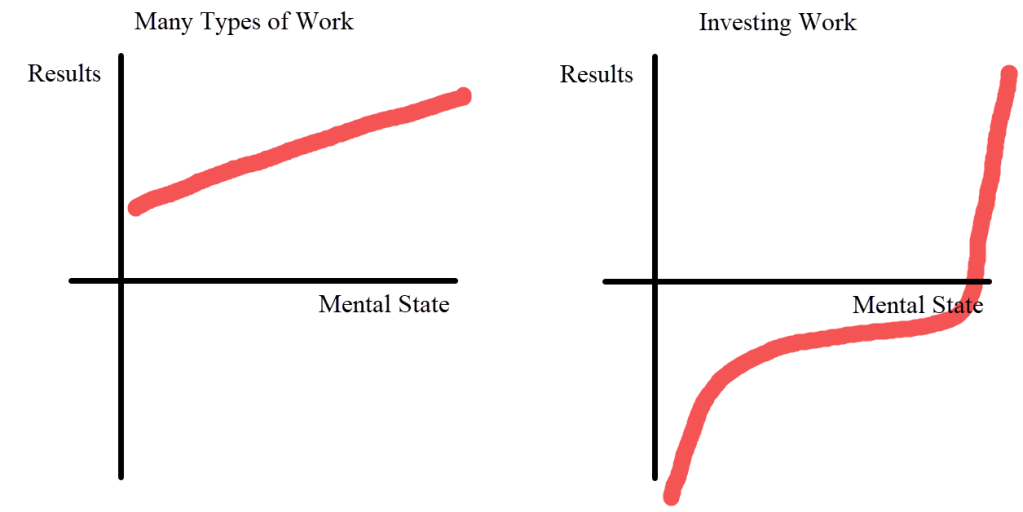

For many types of work, the relationship between effort and results is more or less linear. (See the chart on the left.) The more effort one puts in, the better results one will get. If one puts in more hours, one will get more iPhone assembled, more apples harvested, more dishes washed, more memos written, more spreadsheets built, and so on and so forth. Common sense.

In investing, however, something is going on that is counterintuitive. (See the chart on the right.) If one puts in more effort, one may not actually get better results — an obvious example is that almost all active investment managers underperform stock indexes. On this note, if one puts in no effort, one can still do well — i.e., by index investing, one will receive an outcome that is near-identical to stock indexes, thus allowing the no-effort investor to beat almost all hardworking active investors (as indicated by the red marker high on the y-axis).

Active investing is indeed really hard — just look around, most active managers are not able to beat stock indexes. Clearly, working hard is not enough. The active investing game is so hard that only if an investor puts in an unusually large amount of effort will he or she stand a chance to outperform.

The Relationship Between “Mental State” and “Results”

Here, let’s also start with the chart on the left. For many types of work, one’s mental state has a somewhat limited bearing on the outcome. If one is feeling down — say, one is feeling just “meh” about everything that day — he or she probably can still assemble iPhones, harvest apples, wash dishes, and use Word and Excel to churn out memos and spreadsheets. The person may miss a thing or two here and there but will still get a lot of the things done.

However, in investing, the relationship between one’s mental state and one’s investment results, I think, looks like the chart on the right-hand side. In a bad mental state, investors make bad moves; a couple of bad moves can result in a few large mistakes; a few large mistakes can compound into substantial losses (so the sinking of the red line to the left).

In a normal mental state, an active investment manager performs at a similar level as his or her fellow active investment managers who, most of the time, are also in a normal mental state. So, for most investors, most of the time, they perform at a similar level, executing similar research processes, prosecuting similar investment strategies — all putting in many, many hours doing more or less the same thing. In this kind of homogenous competition, how can we expect any one of these investors to outperform at all, let alone by significant margins? The most likely outcome is no big wins, no big losses, but a lot of mediocrity. And that is what is happening. Most investors make some money here, lose some money there; they incur commissions, and they charge their clients fees and expenses; all in all, those normal-state investors end up underperforming stock indexes.

The greatest investors, however, operate in a very different mental state — the highest mental state, which then allows these investors to be prescient, to see things coming, to make the right bet, to bet big and win big.

The highest mental state is where the differences lie. But how? Here is the way I see it.

One, in the highest mental state, an investor has the ability to focus in great depth. Focus, to the degree that space no longer exists and time no longer ticks, to the degree that one’s own identity disappears. In that state, the person gets great inner clarity. He or she knows exactly what to do from one moment to the other. He or she knows what needs to be done and how well things are being done. He or she speeds past high obstacles without realizing they were there. Innate understandings arrive and insights are gained. Time is bent and the future is seen. People who have experienced it know what I am talking about here.

Two, in the highest mental state, an investor gains the ability to create a lot of white space in his or her mind. No more concerns. No more anything. It is just pure consciousness, and a lot of white space. Emptiness. Nothingness. That feeling of an altered existence allows for the exploration of concepts, thoughts, and ideas that might seem too strange or too abstract under normal circumstances. Instead of observing exactness, he or she gets to see the underlying forces of nature that drive changes. Then, from there, unusual perception emerges, creativity comes.

Three, the highest mental state allows an investor to be highly self-aware. High self-awareness, in turn, gives the investor the ability to quickly tell whether he or she is currently in that highest mental state or not — i.e., being in that mental state gives you the ability to tell you are in that mental state — it is like a loop that closes onto itself. The investor can quickly identify whether he or she is in a 10 out of 10 mental state, or just something like a 5 out of 10. That is an important mental capability because most people experience something like this: they slip from a 8 to a 2, only to realize it after hours have passed — and by the time they become aware of where they are, a lot of decisions have been made. Because these decisions were made in a suboptimal mental state, many of these decisions may well turn out to be bad ones. In investing, that directly leads to investment mistakes. Therefore, in investing, high self-awareness matters: First-rate investors know that only when they are in their best mental state are they ready to make important decisions.

This point about mental state, I think, may also be a reason why high-performing investment teams do not scale: the more analysts you have on the team (either you want it that way, or your client investors demand it), the greater the chance that someone will be working very hard for you, but doing so in a suboptimal mental state without that person even being aware of it. That analyst thinks he or she is doing the right thing. You probably think so as well. Yet, results prove otherwise. Ask yourself: 1) When was the last time you came across an investment organization with a large number of stock-picking analysts that can still outperform stock indexes? 2) How many investment analysts have Warren Buffett and George Soros had throughout their investing career? For both questions: Not too many; actually, very few.

Summary

To borrow from the Pareto rule (a.k.a., the 80/20 rule): For many types of work, probably, the first half of what you put in will get you 80% of results; the second half will bring you from 80% to 100%.

In active investing, that same relationship just doesn’t exist. The first 50%, 80%, or even 90% bring an investor nothing if just sheer underperformance. It is the last 10% or even the last 1% of what an investor puts in will have the biggest possible impact on the investor’s investing results. To translate: “Doing well” doesn’t matter. “Doing significantly better” matters.

And that “doing significantly better” encompasses at least these three elements: 1) working unusually hard (something physical; probably it can be trained for); 2) operating in the highest mental state (something psychological and biological; probably a person is born with this ability and therefore it cannot be trained for); and 3) stumbling upon some good luck.

I observe myself and I observe others. Through my observations and my own experiences, I see that there is the “invisible path.”

(END)

Nice blog, Jackson! (The first chart is a winner!) Your concept is powerful and nicely expressed. ….another chapter for your book!

Thanks for sharing,

Charley

LikeLike